Just when I thought that suburban living had lost its luster, a bright light is once again shining on homes in the suburbs, small towns and far away places in rural Canada. Who knew? Before the COVID pandemic it appeared that downtown condos, small spaces with little or no gardens, were coveted properties by young and older adults alike.

The fallout from the pandemic has changed everything. Many of us are becoming “more attracted to the space and lower-density populations outside Toronto since COVID-19,” according to newly released Nanos research prepared for the Ontario Real Estate Association (OREA).

Toronto Star Real Estate Reporter Tess Kalinowski adds, “Among those considering a home purchase in the next two years, 61 per cent of online survey respondents agreed or somewhat agreed that COVID-19 has increased their interest in suburban or rural housing. Only 34 per cent said they were more drawn to downtown living since the public health crisis hit.”

My sense is that this change in attitude is partially fueled by the staycations that we’re taking this summer. Since it’s in no one’s interest to venture outside Canada, or even far from home, we’ve found simpler ways to entertain ourselves. Much of that, in this country, can be found outdoors and far from the city lights.

For my family, it was a two-week stay at a quaint chalet in Renfrew County, northwest of Ottawa and east of Algonquin Park. I happen to favour this rugged, sparsely populated, mostly wilderness corner of the province. It brings me in touch with the pioneers who valiantly attempted to clear this land for farming. Most failed, and it’s still possible to see the uneven fences made of rocks that pioneer farmers pitched from the unyielding soil of the Canadian Shield.

A city slicker myself, I mentioned to a long-time resident of Renfrew County how beautiful, how colourful, how artful the rocks are, and he showed no hesitation by replying, “The farmers wouldn’t agree with you.”

For us, being up north was a much-anticipated vacation from COVID. When we settled into our little chalet, near Eganville, nestled on the property of Gerber’s Nursery, we were fed up with isolating inside the house, taking stealth walks while keeping a sharp lookout for others, careful to not get within two metres of anyone. Out in the country, we didn’t bump into anyone, other than friends from Ottawa with whom we spent a most wonderful day swimming and lounging around the guest pool at Gerber’s.

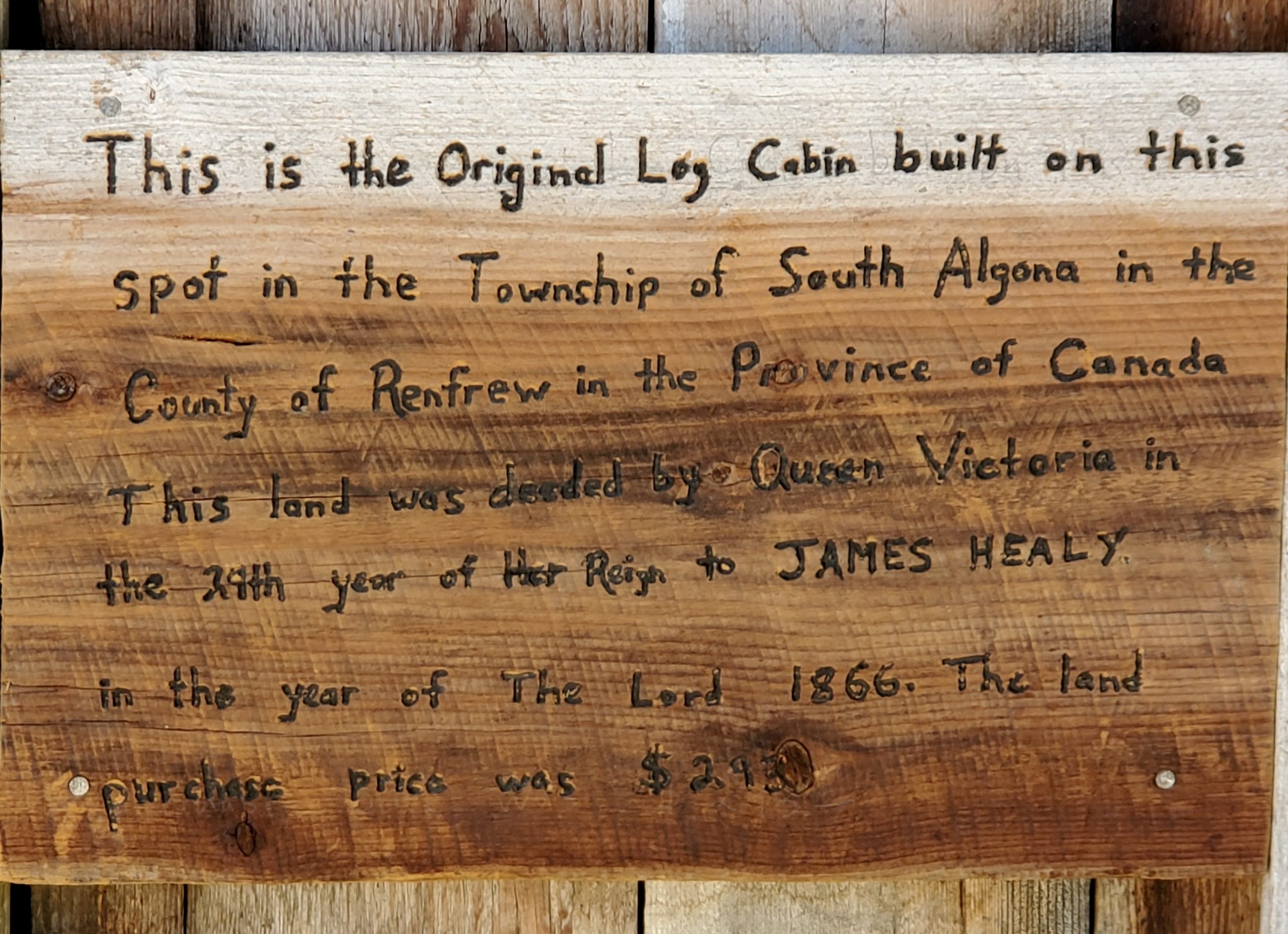

The Gerber family has run their nursery since they fled East Germany in 1956. They’ve built a prosperous business by growing plants and vegetables from seed in the large greenhouses on their 300-acre property. Across from our chalet is the big house where the elder Gerbers, the grandparents, who landed in Canada, lived. And across from the big house is the original log cabin, which displays this sign:

“This is the original Log Cabin built on this spot in the Township of South Algoma in the County of Renfrew in the Province of Canada. This land was deeded by Queen Victoria in the 29th year of her Reign to James Healy in the year of The Lord 1866. The land purchase price was $293.”

While relaxing in Renfrew County these days, there hadn’t been a newly confirmed case of the virus in many weeks. Amidst this vast tract of land, only 2 cases were being treated while we vacationed there.

This sparsely populated wilderness is a world unto itself: quiet, rugged and majestic. Before Confederation in 1867, Canada West was selling an acre of land for about one dollar. Politicians in Upper Canadfda, now Ontario, figured there’d be 8-million settlers drawn to the Ottawa Valley in their lifetimes.

In his book Algonquin Park: a Place Like No Other, Roderick MacKay writes, “The Free Grant system along the colonization roads was intended to entice settlement. All that was required to get a free land grant was to fulfill the requirements of clearing and cultivating 12 acres within four years, and construction of a cabin.”

Of course, the soil was so impenetrable and the climate so punishing that by the mid-1860s, more than two-thirds of the homestead farms had failed, with a quarter of these pioneers not even completing the improvements required to get a patent on their land. Next, the government lured Eastern Europeans to the county, Poles and Germans, mainly when the British immigrants moved on.

Hence, the history of the Algonquin-Renfrew region is mostly about logging, the grand lumber barons and their hardworking lumberjacks who survived in the bush from September to April. (I’ve yet to read a book about the women of the county who kept the home, cared for the children and attended to the farm while surviving the long winter months with their husbands away in the bush.)

In the spring, the rivermen or river drivers, as they were called, walked along the banks of the rivers, such as the Bonnechere, to accompany the thousands of sawlogs downstream to the mills. According to MacKay, “The drive required sureness of foot, tolerance of icy water and courage. In late May and early June, the men were plagued by the Black Fly and the mosquito.”

When logs got stuck, these rivermen risked their lives to get the logs moving again. “There was no workers’ compensation or health insurance if a man got hurt. Burial was often on the river bank….Nearly all waterfalls and rapids on the Madawaska, Petawawa and Bonnechere River have a river driver’s grave nearby,” says MacKay.

More than 150 years later, Renfrew County and westward toward Algonquin Park, the land of the lumberjacks remains sparsely populated. By urban standards, property is inexpensive. No wonder families pressed for space, concerned about putting their children in crowded classrooms or for those who can manage working from home, it’s an option to consider country life. For older Canadians, it can be a refuge from the expenses and constraints of city life.

Before leaving Renfrew County, we drove past a stately 4-season cottage on the mighty Ottawa River outside the town of Deep River. The white cottage pulled at our heartstrings with its wrap-around screened-in verandah. My husband might have made an offer right then and there, but I couldn’t agree. One thing for sure is that we’ll be back in Renfrew County next summer, swimming in Golden Lake, and wondering why we didn’t buy the home that would go for four times the price – or more – in Toronto.

|